Assessment of Antenatal Breastfeeding Education, Early Initiation and Exclusive Breastfeeding practices of mothers attending a secondary healthcare facility in Southern Nigeria

Alphonsus Rukevwe Isara, Makwachukwu Chioma Ekwo

Abstract

Background: Antenatal Breastfeeding education is teaching women about breastfeeding during pregnancy before the baby arrives. The content of breastfeeding education given to mothers during antenatal care visits can play critical role in the adoption of early breastfeeding initiation in the immediate postpartum period and subsequent increase in the rate of exclusive breastfeeding.

Objective: This study assessed the antenatal breastfeeding education, early initiation of breastfeeding and the practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers attending a secondary healthcare facility in Benin City, Nigeria.

Materials and methods: A cross-sectional study utilizing a mixed method approach comprising both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. Mothers who had vaginal delivery were recruited consecutively from the postnatal ward to participate in the study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of Edo State Hospitals Management Board.

Results: A total of 360 mothers aged 18 to 42 years were interviewed. Majority, 334 (92.8%) received breastfeeding education while pregnant, predominantly during ANC, 309 (92.5%). The main contents of the breastfeeding education received were importance of exclusive breastfeeding, 265 (79.3%), and care of breast in preparation for breastfeeding 258 (77.2%). Only 170 (47.2%) prepared their breast for breastfeeding, 133 (36.9%) commenced breastfeeding within one hour of delivery, while 276 (76.7%) practiced exclusive breastfeeding at 6 weeks postpartum.

Conclusion: This study showed that the content of breastfeeding education given to mothers was inadequate. The preparation of the breast for breastfeeding was inadequate and early initiation of breastfeeding following delivery was low. But the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 weeks postpartum was encouraging.

Keywords: Breastfeeding education, Breastfeeding initiation, Exclusive breastfeeding, Antenatal care, Secondary Health Facility, Nigeria.

Introduction

Breastfeeding is a major public health issue considering its role in reducing child morbidity and mortality rates as well as improving maternal health. Breastfeeding newborns as promptly as possible after birth by making the infant receive colostrum which is rich in immunoglobulins and other protective nutrients, significantly enhances their likelihood of continued existence.1,2 Globally, only about 44% of infants aged 0 - 6 months were exclusively breastfed over the period of 2015-2020.3 The prevalence (35%) of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) is low in sub-Sahara Africa.4 According to the 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), Nigeria’s EBF rate remains low with only 29% of babies 0 - 5 months being breastfed exclusively.5 Thus, Nigeria has one of the highest infant and under-5 mortality rates in Africa; 67 per 1000 live births and 132 per 1000 live births respectively.5

Concerning breastfeeding, the recommended practice by the World Health Organization (WHO) is early initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth, EBF for six months and breastfeeding for at least two years after the postnatal period.6 Several short and long term beneficial effects in babies have been linked with appropriate breastfeeding practices.7 Poor breastfeeding practices such as delayed initiation, non-EBF and early weaning can affect infant survival including exposing the child to diarrhea through contaminated water, pneumonia and other infections. Evidence from the National Household’s Surveys in Nigeria indicates that the rate of early initiation of breastfeeding increased from 31.9% in 2003 to 38.4% in 2008 but decreased sharply to 33.2% in 2013, and rose again to 42% in 2018.5

Antenatal breastfeeding education is teaching women about breastfeeding during pregnancy before the baby arrives.8 The knowledge and attitudes of mothers regarding breastfeeding play an important role in influencing breastfeeding choices and increases the mothers breastfeeding self-efficacy.9 Majority of first time mothers are likely to be faced with challenges of initiating breastfeeding and may require postnatal lactation support to initiate breastfeeding especially if not well informed prior to delivery. It is therefore necessary to understand the content of the antenatal breastfeeding education available to expectant mothers in preparation for breastfeeding after delivery of their babies, the breastfeeding initiation experience and EBF practices of mothers who received antenatal breastfeeding education. Although there is a connection between antenatal breastfeeding education and breastfeeding practices, the nature and strength of the connection is unclear.10 Previous studies had looked at the factors affecting breastfeeding, influence of mothers educational level on breastfeeding, evaluation on the knowledge, attitude and practice of EBF, breastfeeding education for increased breastfeeding duration amongst others, however, there is limited report on studies that examined the information available to expectant mothers on breastfeeding.

The content of the breastfeeding education given to mothers during antenatal visits play a critical role in the adoption of early breastfeeding initiation in the immediate postpartum period and subsequent increase in the rate of EBF, among mothers. Therefore, this study assessed the antenatal breastfeeding education, early initiation of breastfeeding and the practice of EBF at 6 weeks postpartum among mothers attending a secondary health facility in Benin City, Nigeria.

Methodology

Study area and design

This facility-based cross-sectional study was carried out in Central Hospital Benin City, in southern Nigeria, from January to December 2021. The hospital is a secondary healthcare facility offering maternity care in Benin City. The Obstetrics and Gynecology department of the hospital renders antenatal, delivery and postnatal services. There are a total of 21 nurses: 13 at the antenatal and eight at the postnatal sections respectively. The hospital practices the traditional approach of antenatal care (ANC). The ANC is scheduled for five days in a week: one booking day and four days for clinic and health education. The services available include prenatal checkup and health talk on nutrition, breastfeeding, retroviral screening and counseling for prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV, personal hygiene, signs of labour, among others. These services are rendered routinely with no schedule attached to a particular day. There is an average of 150 ANC weekly registrations with an average of 150 women attending antenatal clinic daily. The delivery section has six delivery beds and nine beds for immediate post-delivery care before transfer to the postnatal ward. An average of 10 deliveries takes place daily in the hospital. The postnatal ward consists of two wards: the maternal surgical ward and the non-complications ward, and each ward has 22 beds. Postnatal checkup holds once in a week on Thursdays.

Study population

This comprised of women who had vaginal delivery without complications in the hospital. Only women who attended at least eight sessions of ANC in the hospital and had singleton delivery were recruited for the study. Mothers of preterm babies, those whose babies were admitted in the Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU), and those who had complications following delivery such as severe anemia, postpartum hemorrhage, postpartum blues or psychosis were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination and recruitment

The sample size was calculated using the sample size formula for single proportion.12 The following assumptions were made: a prevalence (p) of 0.29 (29%) being the proportion of exclusively breastfed babies in Nigeria as documented in the 2018 NDHS,5 confidence interval of 95% and an error margin of 5%. Thus, the sample size calculated was 317, but this was rounded up to 349 in anticipation of a non-response rate of 10%. However, a total of 360 mothers who met the inclusion criteria were recruited consecutively from the postnatal ward of the hospital to participate in the study.

Data collection

Data was collected using both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods.

Quantitative data: A researcher-administered questionnaire adapted from UNICEF breastfeeding documents - key message booklet on community infant and young child feeding, and other relevant literature ‘how to breastfeed your baby’ was the tool for data collection immediately after delivery (within 48 hours) and at 6 weeks postpartum. With the consent of the mothers, their telephone contacts were collected. They were followed up through telephone calls and text messages to remind them of their postnatal clinic. The questionnaire consists of seven sections: section one to six of the questionnaire was administered to mothers immediately after delivery and comprised of the following: socio-demographic characteristics of study participants, source of breastfeeding education, content of breastfeeding education, influence of antenatal breastfeeding education on breastfeeding practice, experience of mothers in initiation and practice of breastfeeding, and factors influencing breastfeeding education. Section seven of the questionnaire was administered to mothers at 6 weeks postpartum during their postnatal visit. It contained questions on post-delivery breastfeeding practices and experiences.

Quantitative data: A non-participant observation technique was employed to collect the qualitative data. One of the researchers acting as a mystery client attended eight sessions of ANC in the hospital in line with WHO standard of essential ANC (one contact in the first trimester, two contacts in the second trimester and five contacts in the third trimester), and completed the observational checklist during the ANC health education sessions. The checklist assessed the content of antenatal breastfeeding education given to mothers and the mode of delivery of the information during ANC, and this comprised of eight sections viz: initiation of breastfeeding, breastfeeding assessment, exclusive breastfeeding, prevention and management of difficulties while breastfeeding, complementary feeding, breastfeeding and birth control, breastfeeding while HIV positive, and assessment of ANC breastfeeding education.

Both the quantitative and qualitative data collection tools were pretested in a Specialist Hospital in Benin City and necessary adjustments were made before the study. Two trained postgraduate students of the University of Benin assisted with data collection.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was done using IBM SPSS version 26 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The outcome variables included: source of breastfeeding education, early initiation of breastfeeding, practice of EBF and factors influencing breastfeeding practice. The association between the socio-demographic characteristics and the outcome variables were tested using the Chi square test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of Edo State Hospital Management Board, Benin City (protocol number: A732/T/1). Institutional permission was also obtained from the Medical Director of Central Hospital Benin. A written informed consent was obtained from the participants after the assurance of confidentiality.

Results

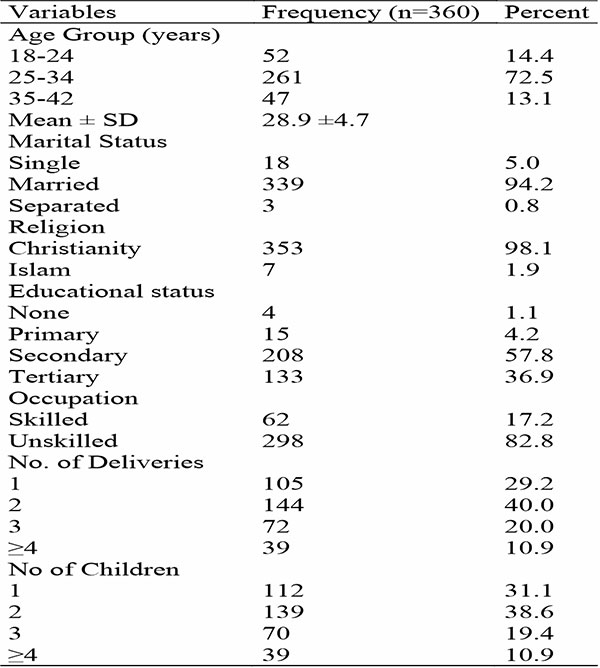

A total of 360 mothers whose age ranged from 18 to 42 years, with a mean age of 28.9 ±4.7 years participated in the study. More than two-third, 261 (72.5%) were within the age group of 25-34 years and most, 339 (94.2%) were married. A higher proportion, 208 (57.8%) of them had secondary school level of education, while few, 4 (1.1%) had no formal education. Majority, 298 (82.8%) of the mothers are unskilled: this comprised those that are hairstylist, traders, tailors, housewives, caterers and petty traders. One in ten, 39 (10.9%) of the mothers had delivered four times or more and correspondingly had four or more children (table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

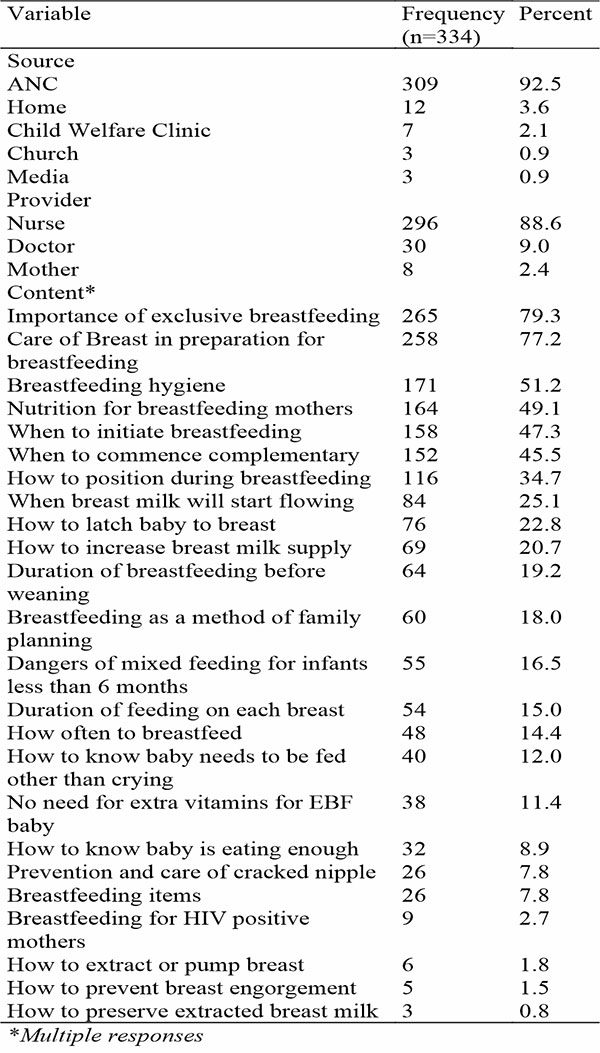

Majority, 334 (92.8%) of mothers responded in the affirmative that they received breastfeeding education while pregnant. Table 2 shows the sources, provider, and content of breastfeeding education received by the mothers. Similarly, 309 (92.5%) mothers received breastfeeding education at ANC health talk session with nurses, 296 (88.6%) and doctors, 30 (9.0%) being the main providers of breastfeeding education. The predominant contents of the breastfeeding education received by the mothers were: importance of EBF, 265 (79.3%), care of Breast in preparation for breastfeeding, 258 (77.2%), breastfeeding hygiene, 171 (51.2%), nutrition for breastfeeding mothers, 164 (49.1%), when to initiate breastfeeding, 158 (47.3%), when to commence complementary, 152 (45.5%), and how to position during breastfeeding, 116 (34.7%). Few mothers received education on breastfeeding for HIV positive mothers, 9 (2.7%), how to prevent breast engorgement, 5 (1.5%), and how to preserve extracted breast milk, 3 (0.8%).

Table 2: Sources, provider, and content of breastfeeding education received by the mothers

The non-participant observation showed that health talks focusing on different topics were delivered to women by one or two facilitators, followed by question-and-answer sessions. The duration of the health talk sessions is usually between 15 to 30 minutes. For the eight ANC sessions attended, it was observed that a public address system was not used during the health talk, and most times the facilitator’s voice could not be heard depending on mothers’ sitting position in the ANC hall. The most common topics during the antenatal health talk were signs of Labour, nutrition in pregnancy, personal hygiene, and care of the newborn. Breastfeeding was not specifically treated as a topic, but the facilitator(s) while talking about feeding of newborns mentioned the following: “Only breastfeeding is allowed for the feeding of new born”, “The earlier the breast is introduced, the faster the breast milk will start coming”, “Breastfeeding position is sitting down and not lying down”, “After feeding the baby gently rub the back for the baby to belch”.

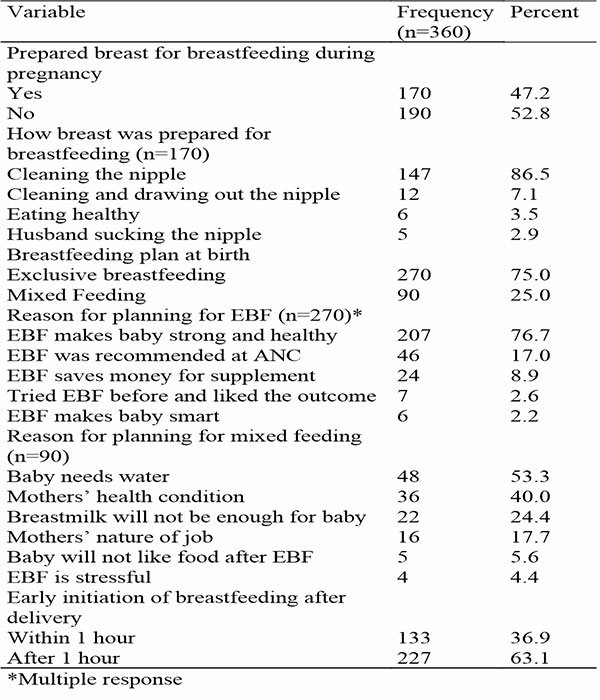

Less than half of the mothers, 170 (47.2%) prepared their breast for breastfeeding while pregnant, predominately by cleaning the nipples, 147 (86.5%), while 270 (75.0%) of them planned to breastfeed exclusively after delivery. The reasons given by mothers who planned to engage on EBF included the fact that EBF makes baby strong and healthy, 207 (76.7%), was recommended at ANC, 46 (17.0%), saves money for supplement 24 (8.9%), and makes baby smart 6 (2.2%). On the other hand, for those who planned mixed feeding, their reasons were mainly that the baby needs water, 48 (53.3%), mothers’ health condition, 36 (40.0%), breastmilk will not be enough for their baby, 22 (24.4%), and EBF is stressful, 4 (4.4%). Only little more than a third of the mothers, 133 (36.9%) commenced breastfeeding within one hour of delivery (table 3).

Table 3: Preparation for and early initiation of breastfeeding by mothers

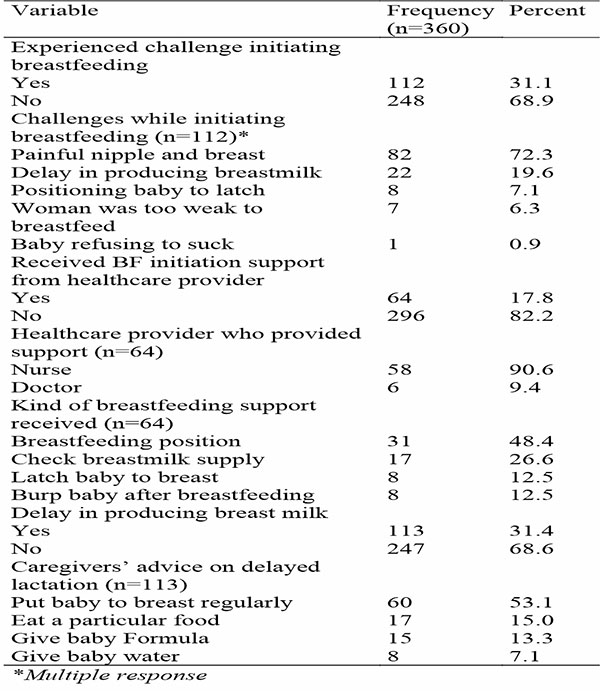

The experiences of mothers in initiating breastfeeding are shown in table 4. More than two-thirds of the mothers, 248 (68.9%) did not experience any challenge in initiating breastfeeding after delivery. However, among the almost a third, 112 (31.1%) who had challenges, painful breast and nipples, 82 (68.3%), delay in producing breast milk, 22 (18.3%), and difficulty positioning baby to latch, 8 (6.3%) were reported. Few, 64 (17.8%) mothers reported receiving breastfeeding support from healthcare providers, of which a higher proportion, 31 (48.4%) and 17 (26.6%) were assisted on breastfeeding position and to check for breast milk supply respectively. Similarly, almost a third, 113 (31.4%) of the mothers experienced delay in producing breast milk. On these, more than half, 60 (53.1%) were advised by their caregivers to put baby to breast regularly while 15 (13.3%) and 8 (7.1%) were advised to give baby formula and water respectively.

Table 4: Experiences of mothers in initiating breastfeeding

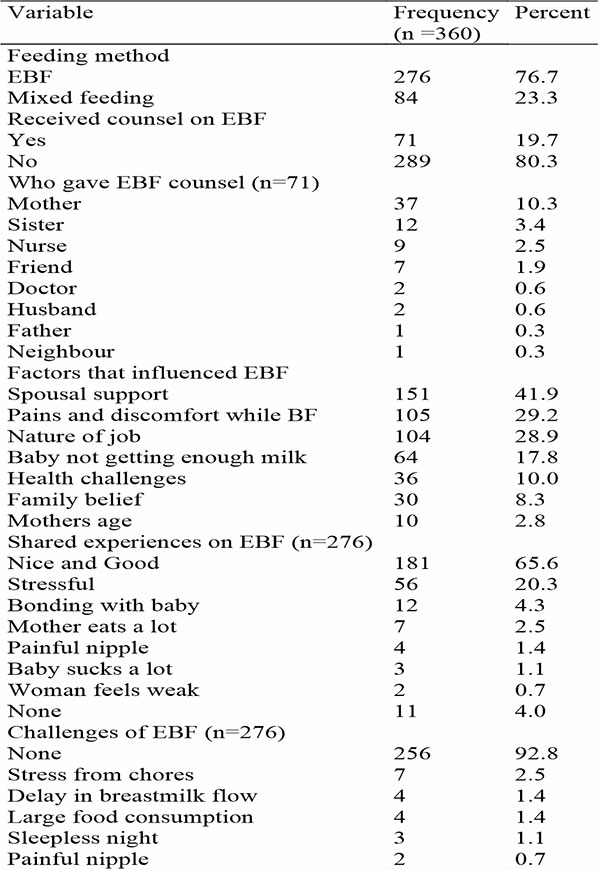

Table 5 shows the EBF practices of mothers at 6 weeks postpartum. Majority, 276 (76.7%) reported that they exclusively breastfeeding their babies, while 84 (23.3%) reported using mixed feeding method, either breast milk and only water or breast milk, water and breast milk supplement. Few, 71 (19.7%) of the mothers received counsel on EBF mainly from their mothers, 37 (10.3%) and sisters, 12 (3.4%) within the 6 weeks postpartum. Spousal support, 151 (41.9%), reported pains and discomfort, 105 (29.2%), and nature of their job, 104 (28.9%) were the predominant factors reported by the mothers to have influenced their practice of EBF. Two-thirds, 181 (65.6%) of the mothers reported having good experience with EBF, 56 (20.3%) reported having a stressful experience, while 12 (4.3%) reported that EBF promoted bonding with baby. However, few, 4 (1.4%) experienced painful nipple with EBF. Most of the mothers 256 (92.8%) did not report any challenges with EBF. However, few mothers reported that combining house chores and EBF was stressful to them, 7 (2.5%). Delay in producing breast milk, 4 (1.4%), sleepless nights, 3 (1.1%), and painful nipple, 2 (0.7%) were other challenges reported by the mothers.

Table 5: Exclusive breastfeeding practices of mothers at 6 weeks postpartum

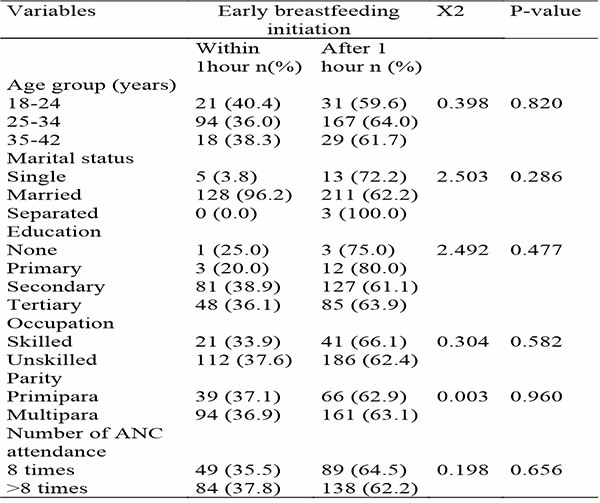

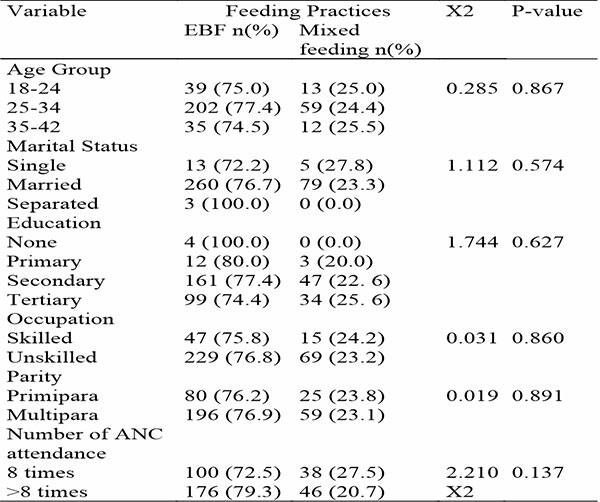

Tables 6 and 7 shows the association between the socio-demographic characteristics of the mothers and early initiation of breastfeeding and breastfeeding practices at 6 weeks postpartum respectively. Apart from most married mothers, 128 (96.2%), the proportion of mothers who initiated breastfeeding within one hour was similar across the socio-demographic characteristics. Similarly, apart from the decreasing trend observed with increasing level of education of the mothers, the proportion of mothers who practiced EBF at 6 weeks postpartum was similar across the socio-demographic characteristics. Generally, there was no statistically significant association between the socio-demographic characteristics of the mothers and their initiation of breastfeeding and the practice of EBF at 6 weeks postpartum.

Table 6: Socio-demographic characteristics and early initiation of breastfeeding

Table 7: Socio-demographic characteristics and feeding practices at 6 weeks postpartum

Discussion

Breastfeeding is very critical to the health of both the baby and mother. As simple as breastfeeding may appear, it requires in-depth information and some level of skills to be able to practice it effectively, which is why it is essential to provide antenatal breastfeeding education to pregnant mothers to adequately prepare them to breastfeed their babies after delivery. The findings of this study showed that the breastfeeding education given to mothers was unstructured, poorly delivered, and inadequate in terms of content. The preparation of the breast for breastfeeding and early initiation of breastfeeding following delivery was low. However, the rate of EBF practice by the mothers at 6 weeks postpartum was encouraging, but not without some challenges.

In this study, it was observed that not all the mothers received breastfeeding education from the ANC clinic, and only few received information on when to initiate breastfeeding and how to position the baby during breastfeeding. This finding suggests that a woman can attend 8 ANC sessions while pregnant and still not receive adequate breastfeeding education. This situation may have resulted from the fact that the mode of delivery and the general environment of the ANC health talks were sub-optimal in this study. This has serious implications for preparation for breastfeeding, early initiation of breastfeeding after delivery, and the practice of EBF as recommended by the WHO. This finding corroborated the results of a study in Oyo State, Nigeria, which showed that the content of the antenatal education given to pregnant mothers attending ANC clinic was not structured to provide balanced information for a positive pregnancy outcome.12 A well delivered antenatal breastfeeding education using acceptable media is a veritable tool to achieve effective breastfeeding of newborns and EBF. A study in Malaysia found that mothers perceived antenatal breastfeeding education as useful and having received it appears to be associated with EBF up to the first 8 weeks postpartum.13 A person-centered breastfeeding education during the antenatal period should complement the traditional methods of health talks during ANC sessions to ensure that all mothers who attended ANC receive the message. The fact that almost all mothers in our environment have a mobile phone can be leveraged upon to promote breastfeeding education as breastfeeding education videos can be sent to their phones. The usefulness of video-assisted breastfeeding education had been reported in previous studies.14,15

In this study, less than half of the mothers prepared their breast for breastfeeding while pregnant. This is an indication that most of the mothers may not be informed on breast preparation in readiness to breastfeeding after delivery. This may be a precursor to delayed initiation of breastfeeding after delivery especially among primiparous mothers with any form of breast abnormality. A study in Haryana, India, reported that under or no preparedness of the mothers for breastfeeding including identification of abnormalities such as inverted and retracted nipple were barriers to early initiation and continuation of breastfeeding.16 A related worry from the results of this study is the fact that, one quarter of the mothers intended to practice mixed feeding after delivery. This goes to show that as old as the EBF campaign, it is yet to sink into the hearts and minds of mothers in our environment. Thus, Nigeria has one of the lowest rates of EBF in sub-Saharan Africa.5 A high prevalence of mixed infant feeding practices among mothers had also been reported in South Africa.17,18 It is imperative for healthcare providers to step up the game through community and stakeholder engagements to overcome the multiple barriers to EBF in order to usher in an improvement in infant feeding indices in Nigeria.

An abysmally low proportion of mothers received breastfeeding initiation support from healthcare providers and correspondingly only slightly more than a third of the mothers initiated breastfeeding within one hour in this study. This worrisome finding which is comparable to a previous study in Edo State, Nigeria,19 may have arisen from the delay in handing babies over to their mothers immediately after delivery as practiced in some hospitals, the claims of babies sleeping, mothers not producing breast milk and mothers feeling weak to attempt breastfeeding. A study in Cameroon reported that caesarean delivery, the belief in “spoiled milk”, lack of knowledge about the time to initiate breastfeeding, baby asleep, and lack of instruction given to the mother by the health staff were the main reasons for delaying breastfeeding initiation.20 A scoping review of early breastfeeding practices in sub-Saharan African countries identified similar household, maternal, and health service characteristics as determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding by mothers.21 These unjustifiable reasons for delay in initiation of breastfeeding reinforces the important role healthcare providers should play in ensuring the practice of early initiation of breastfeeding by mothers and supporting the entire process.

The initiation of breastfeeding is not without challenges especially for primiparous mothers. In this study, mothers experienced the following challenges while initiating breastfeeding: painful nipple and breasts, delay in producing breast milk, and positioning baby to latch. However, very few of the mothers received lactation support from healthcare providers. These findings buttress the need for healthcare providers to provide timely, effective, and patient-centered lactation support to mothers by helping them to position the baby to breastfeed, ensuring the baby’s mouth latches well on the nipple to prevent cracked nipples, and ensuring they continue to put baby to breast to help increase production of breast milk.

The high prevalence rate of EBF at 6 weeks postpartum was commendable, but slightly higher than the proportion of those who expressed their intention to practice EBF despite the fact that only few mothers received counselling on EBF in this study. This may be attributable to the breastfeeding education on the importance of EBF received by mothers during ANC, and the post-delivery counselling on EBF given by healthcare providers, family members, and relatives. This implies that both healthcare providers, families and relatives can influence mothers’ EBF practice. This is encouraging as early infant mixed feeding may lead to less intake of breast milk which can result in reduced lactation and infant under-nutrition. The mothers who practiced EBF in this study gave positive testimonies about it. However, few challenges such as delay in breast milk production, stress from household chores, discomfort from painful nipple and sleepless nights, were reported. Similar challenges have also been reported by mothers in other African countries and other parts of the world.22-24 This underscores the need for a focused individualized intervention targeted at maternal factors that influence the practice of EBF.

Study strength and limitations

This was a cross-sectional study utilizing a convergent, parallel mixed method approach. The information provided by the mothers regarding breastfeeding information provided during ANC and the practice of EBF may have been prone to recall bias and social desirability.

Conclusion

This study showed that the breastfeeding education given to mothers was unstructured and inadequate in terms of content. The mode of delivery and the environment in which breastfeeding education takes place during ANC were sub-optimal. The preparation of the breast for breastfeeding was inadequate and early initiation of breastfeeding following delivery was low. A lower proportion of the mothers received lactation support from healthcare providers while initiating breastfeeding. The rate of EBF practice by the mothers at 6 weeks postpartum was high, but not without some challenges. Spousal support, breast pains and discomfort, and mothers’ nature of job were the predominant factors that influenced the practice of EBF.

We recommend that a focused, person-centered approach should be employed by healthcare providers to deliver a structured breastfeeding education to mothers during ANC sessions. The facilities for delivering breastfeeding education messages should be improved upon to ensure that the message reaches all mothers who get in contact with the healthcare facility during pregnancy. Policies aimed at early initiation of breastfeeding should be effectively implemented in the healthcare facilities.

References

- Garcia CR, Mullany LC, Rahmathullah L, Katz J, Thulasiraj RD, Sheeladevi S, et al. Breast-feeding initiation time and neonatal mortality risk among newborns in South India. Journal of Perinatology. 2011;31(6):397-403. DOI: 10.1038/jp.2010.138.

- NEOVITA Study Group. Timing of initiation, patterns of breastfeeding, and infant survival: prospective analysis of pooled data from three randomised trials. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(4):e266-75. DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)00040-1.

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheet on Infant and Young Child Feeding. 2023. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding.

- Elyas L, Mekasha A, Assfa E. Exclusive Breastfeeding Practice and Associated Factors Among Mothers Attending Private Paediatric and Child Clinics. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Paediatrics. 2017;2017:8546192. DOI: 10.1155/2017/8546192.

- National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. In Abuja, Nigeria, Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International. 2019.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendation on postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn. WHO. Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. Available from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506649.

- Hansen K. Breastfeeding: a smart investment in people and in economies. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):416. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00012-X.

- Lumbiganon P, Martis R, Festin MR, Ho JJ, Hakimi M. Antenatal Breastfeeding Education for Increasing Breastfeeding Duration. Cocharane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;12:(CD006425). DOI: 10.1002/14651858.pub4.

- Dennis CL. Theoretical underpinnings of breastfeeding confidence: a self-efficacy framework. J Hum Lact. 1999;15(3):195-201. DOI: 10.1177/089033449901500303.

- Serçekus P, Mete S. Effects of antenatal education on maternal prenatal and postpartum adaptation. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(5):999-1010. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05253.x.

- Kadam P, Bhalerao S. Sample size calculation. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1(1):55-57. DOI:10.4103/0974-7788.59946.

- Akinwaare MO, Oyebode AO, Brown VB, Ogunniran AA, Adeleye KK. Content of Antenatal Education and Modalities of Delivery among Nurses in Oyo State, Nigeria. European Journal of Medical and Health Sciences. 2021;2:185-191. DOI: 10.24018/ejmed.2021.3.2.502.

- Tan ML, Foong SC, Ho JJ, Foong WC, Mohd R, Harun Z. Postpartum women’s perception of antenatal breastfeeding education: a descriptive survey. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2020;15:85. DOI: 10.1186/s13006-020-00328-2.

- Metin A, Baltaci N. The effects of video-assisted breastfeeding education given to primiparous pregnant women on breastfeeding self-efficacy: randomized control study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2024;24:142. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-024-06317-1.

- Puspitasari D, Sunarsih T. The Effectiveness of Education Video and Booklet Media for Pregnant Mothers Knowledge on Preparation of Breastfeeding Practice. Advances in Health Sciences Research. 2020;34:219-221.

- Majra JP, Silan VK. Barriers to Early Initiation and Continuation of Breastfeeding in a Tertiary care Institute of Haryana: A Qualitative Study in Nursing Care Providers. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(9):LC16-LC20. DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19072.8559.

- Semenekane NM, Witten CB, Swanepoel E, Kruger HS. Sociodemographic factors associated with mixed-feeding practices among a cohort of mothers with infants aged 4 - 14 weeks in Tlokwe subdistrict, North West Province, South Africa. Afr J Child Health. 2022;16(4):192-197. DOI: 10.7196/SAJCH.2022.v16.i4.1808.

- Mgolozeli SE, Shilubane HN. Factors contributing to mixed feeding practices amongst mothers and caregivers of neonates at Maloma village, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Phys. Health Edu. Recreat. Dance. 2015(Supplement 1:1):84-94.

- Atimati AO, Adam VY. Breastfeeding Practices among Mothers of children aged 1–24 Months in Egor Local Government Area of Edo State, Nigeria. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2018;33(1):10-16. DOI: 10.1080/16070658.2018.1493071.

- Nguefack F, Ngwanou DH, Kamsu Moyo GP, Ejake L, Mah EM, Wafeu G, et al. Reasons for Delayed Breastfeeding Initiation among Newly Delivered Women in Two First-Category Hospitals in Yaounde, Cameroon. Open Journal of Pediatrics. 2020;10:474-485. DOI: /10.4236/ojped.2020.103048.

- Shimizu M, Nakat Y, Takahashi K. Current findings and gaps in early initiation of breastfeeding practices in sub-Saharan African countries: A scoping review. J Glob Health 2023;13:04036. DOI: 10.7189/jogh.13.04036.

- Tampah-Naah AM, Kumi-Kyereme A, Amo-Adjei J. Maternal challenges of exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding in Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2019:14(5):e0215285. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215285.

- Vázquez-Osorio IM, Vega-Sánchez R, Maas-Mendoza E, Heller Rouassant S, Flores-Quijano ME. Exclusive Breastfeeding and Factors Influencing Its Abandonment During the 1st Month Postpartum Among Women From Semi-rural Communities in Southeast Mexico. Front. Pediatr. 2022;10:826295. DOI: 10.3389/fped.2022.826295.

- Wang Y, Mao K, Chu M, Lu M. Perinatal maternal factors influencing postpartum feeding practices at six weeks. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2024;24:514. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-024-06711-9.